Harmonic chemistry examines the nature of the periodic table from the perspective of musical resonance. Consequently we now have a new explanation for why element 43 and 61 are unstable.

Overview

The periodic table, a cornerstone of modern chemistry, offers a comprehensive catalogue of the elements that make up our material world. Each atom, with its unique properties and composition, contributes to the complex tapestry of the universe. Yet, nestled within this orderly arrangement lies a puzzling anomaly.

Atoms, the building blocks of matter, display an astounding range of characteristics. Beginning with the simplest hydrogen atom, consisting of a lone proton, elements progress systematically, each identified by its atomic number or the number of protons it holds. This structured evolution forms the basis of the periodic table, providing scientists with a blueprint of chemical elements.

Curiously, this harmonious progression encounters a stumbling block at element 43, where instability abruptly sets in. This instability appears once more at element 61, disrupting the predictable pattern observed throughout the periodic table. Beyond element 83, radioactive elements dominate, leaving the quest for stable atoms seemingly unresolved. As a result, the periodic table is currently limited to 81 known stable elements.

While scientists have long sought to unravel the mystery surrounding these undefined elements, present theories like ‘Magic Numbers’ fall short in providing a satisfactory explanation for their existence. However, Harmonic Chemistry presents a compelling alternative, grounded in the principles of musical theory and resonance.

Drawing a parallel between the periodic table and a piano keyboard, Harmonic Chemistry infuses the study of chemical structure with an element of fascination and accessibility. Just as the arrangement of keys on a piano follows a harmonic relationship, the elements on the periodic table possess intricate connections based on the principles of resonance. This innovative perspective allows for a deeper understanding of the periodic table, making it both engaging and comprehensible.

Present scientific theory has yet to provide a satisfactory answer as to why this should be. The present theory of ‘Magic Numbers’ cannot account for these phenomena.

Harmonic Chemistry provides a simple-to-understand reason based on the concepts of musical theory and resonance. From this, we can understand the periodic table in terms of a piano keyboard, which makes learning the chemical structure of the universe, both fun and easy to learn.

THE

Concept

What is Harmonic Chemistry?

Harmonic Chemistry is a revolutionary concept that unifies the colours of the visible spectrum and the structure of the periodic table through simple musical principles. This unification offers the perfect complimentary study of Atomic Geometry. Both present a concise description of the atomic structure. However, Harmonic Chemistry extends the application of Atomic Geometry in order to explain the interactions of larger molecules.

Harmonic Chemistry uses music theory to map the first 81 stable elements of the periodic table. The model can be explained using an ordinary musical keyboard as a template. It can easily explain the reasons for the anomalies in the electron cloud that defy the Aufbau principle. and why element 43 and 61 should be non-stable atoms.

Musical Construction

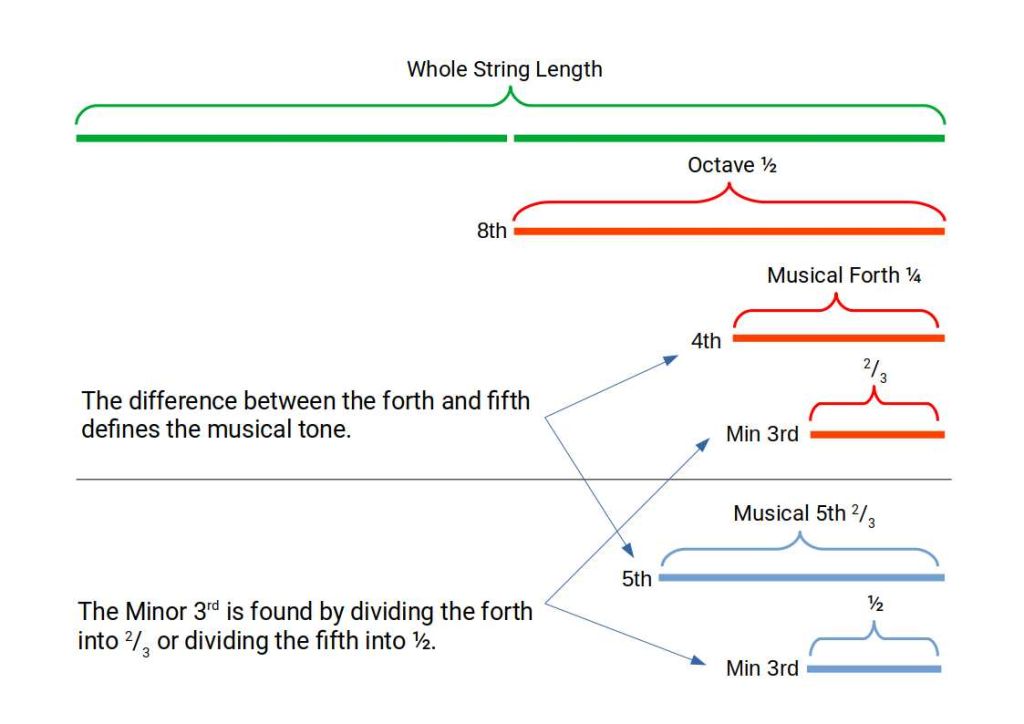

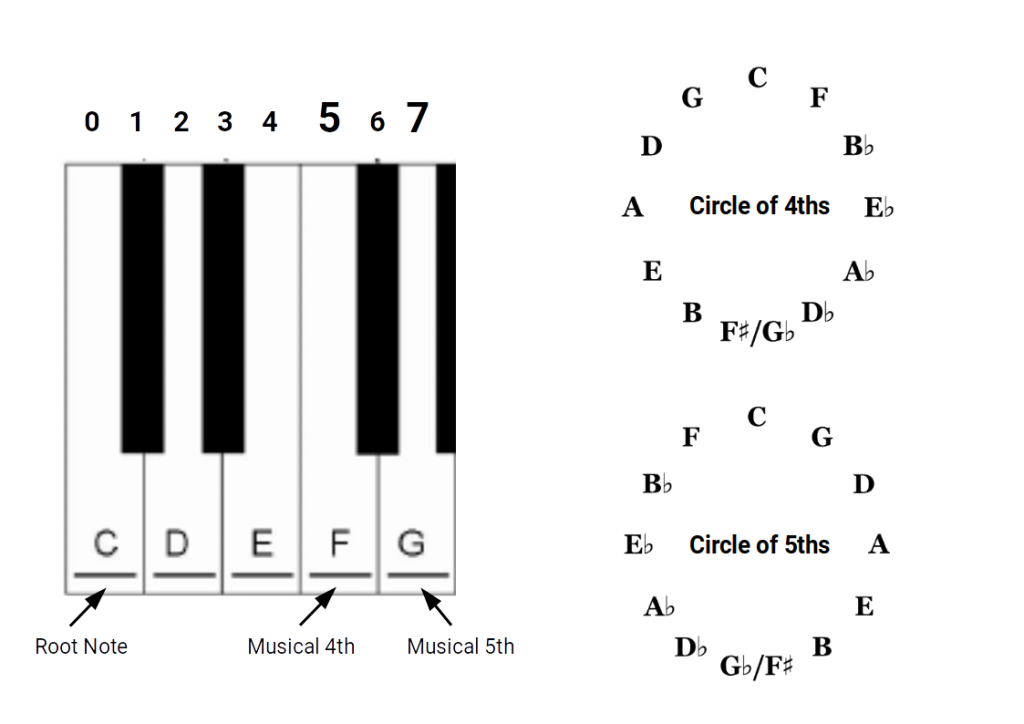

All music is derived through the division of a string into 2 or 3. When a string is divided in half the tone doubles in pitch forming an octave, the 8th note in a scale. Dividing again quarters the string forming the musical 4th. When we divide the sting into three, we define the musical 5th. The difference between the 4th and the 5th forms a tone. An example of a musical tone is found as the interval between two white notes on a keyboard, with a black note in between. The interval between the white and black note is called a semitone. Finally we can divide a 4th into 3 or a 5th in half to create the Minor 3rd.

The 4ths and 5th create an interval that is based on the whole length of the string. These two intervals are used to create the circle of 4ths and 5ths, that defines the 12 notes of the musical scale. 7 white and 5 black. The musical 4th is 5 semitones higher than the root note, whereas the musical 5th is found to be 7 semitones above the root.

These two intervals form a circle of 4ths and 5ths. Each employs the same 12 notes in the same sequence, with the only difference being the direction around the circle. This is because there are 12 notes on the scale, yet the interval created by the 4th and 5th produces the tone, which goes on to generate the 7 notes of a musical scale. The confusion often arises as musically we only use a 7 note scale, whereby 5 notes are not included. The division of the 12 notes is therefore 5 black notes to 7 white.

81 Stable elements

Whilst the Universe might appear to be complex, its foundations are actually rather limited. Everything is made of atoms, that come in different types. What determines the fundamental qualities of each one is the number of electrons and protons it comprises. Interestingly, electrons and protons, under normal conditions, are always equal. These Atomic Numbers define the different elements of the Periodic Table such as hydrogen (1), carbon (6), nitrogen (7), and oxygen (8).

If we count up the number of stable atoms, we find they total 81. All other atoms are non-stable. These are the radioactive elements that radiate their energy, as they decay into stable atoms, normally lead (82) or bismuth (83), found at the end of the series of stable elements.

From Sound to Matter

Missing elements

It is a curious fact the Element 43 and 61 are not stable atoms. The reason for this anomaly is not clearly defined by modern scientific thinking. The current theory of Magic Numbers is not adequate to describe this phenomenon.

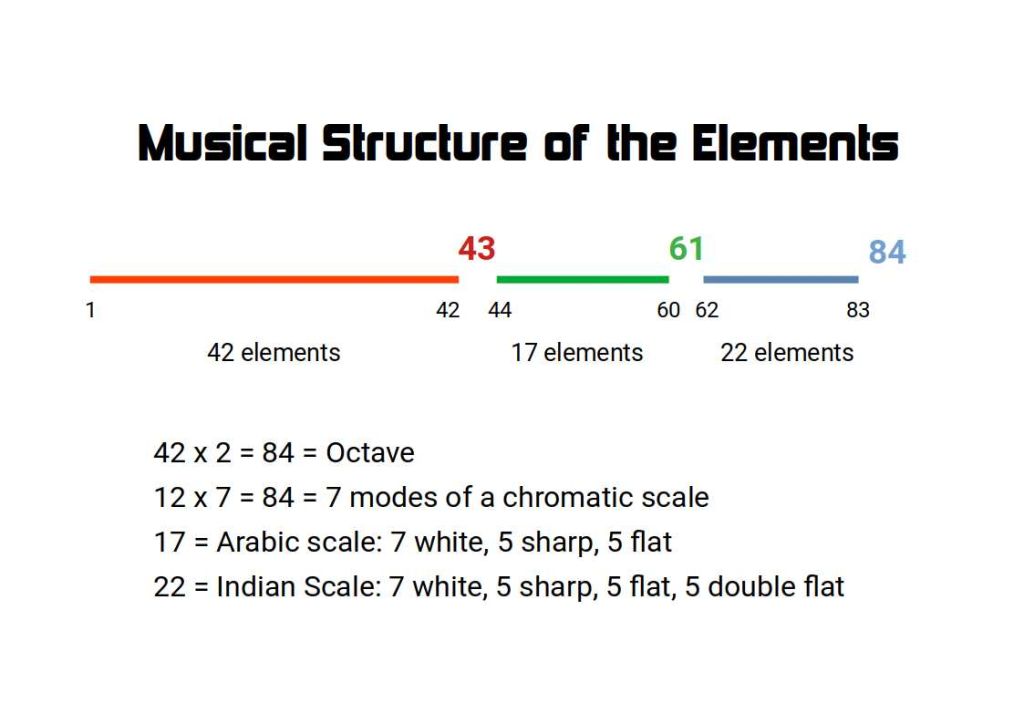

Harmonic Chemistry suggest that the reason these two atoms are unstable, can be easily explained in terms of Music. The last stable element is 83 after which element 84 begins the series of naturally radioactive elements. This value is 12 x 7 which are found to produce the musical scale. Furthermore, we find that 84 84÷2= 42. This is the last stable atom before element 43, which is unstable. Just like a musical octave, the periodic table has a break in its mid-point.

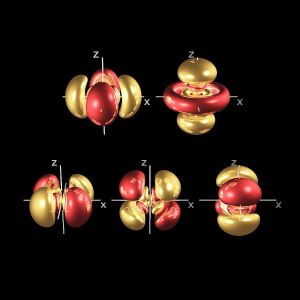

If we divide 84 into 3 we get 28, which is a third of the way through. Two thirds creates the musical fifth and is therefore represents element 56 (28×2). This is the ‘final boundary’ of the atom, formed by a pair of S-orbitals in the 6th shell. All subsequent electrons form in a lower energy shell. For example, the F-Orbitals (57-70) form in the 4th shell, and the final set of D-Orbitals (71-80) appear in the 5th shell.

By placing the different orbitals types, S, P, D and F, in the correct shell number, the traditional periodic table exhibits a slightly different appearance.

Orbitals: Yellow = S Red= P Green = D Blue = F Black = Non stable.

Note that the S orbitals (Yellow) appear further from the atomic nucleus than other orbital types.

In the image above, we can see that the D-orbital elements appear in shells 3 to 5, whereas the F-orbitals appear in the 4th shell. Notice how the radioactive elements 43 and 61 now appear in exactly the same location, something which is absent from the traditional interpretation of the periodic table.

Arabic Scales

Sharps and flats are not the same thing. Musical notes are logarithmic in nature. When we observe the note spacings on a guitar, we can see that the higher pitch notes occupy a smaller space on the fretboard. Musical scales are created for a specific key. Modern western music uses a tempered scale, that detunes certain notes in order to make allow for simple key changes, without the need to retune the instrument. This avoids the need for musical modes, that exhibit a certain number of sharps or flats.

Middle Eastern scales do not employ the tempered scale, and define the difference between the sharp and flat. This gives the scale 17 notes, (7 white, 5 sharp and 5 flat). After the first non-stable element (43), we find there are 17 more stable atom types, (44-60), which is the number of notes that for the middle-eastern scale.

C, D♭, C♯, D, E♭, D♯, E, F, G♭, F♯, G, A♭, G♯, A, B♭, A♯, B, C

Alexander J. Ellis refers to a tuning of seventeen tones based on perfect fourths and fifths as the Arabic scale. In the thirteenth century, Middle-Eastern musician Safi al-Din Urmawi developed a theoretical system of seventeen tones to describe Arabic and Persian music.

Vedic Scales

The Vedic system of Shruti is based upon the 22 note scale, which is suggest to be the smallest increment the ear can discern. This differs from the Swara, which is found as the 7 notes that form a scale. The Shruti is found as additional incremental possibilities of the incidental (black notes) on the tempered scale.

When compared to the 12 note scale, we find that the root (C) and fifth (G) are the only notes that do not exhibit a dual characteristic.

After the second non stable elements (61) on the periodic table, we find there are a total of 22 more stable atoms types. After this 83 marks the end of stable elements.

THE

Conclusion

- The missing elements on the periodic table can be defined by musical resonance and ratio.

- This provides a mathematical foundation that can solve this scientific enigma.

Carry On Learning

This article is part of our new theory, of the Elements

browse more interesting post from the list below

D-Orbital Geometry – Part 2

The 2nd set of D-orbitals contain various anomalies that are explained by the Geometric model of the atom. Part 2 of 3.

D-orbital Geometry – Part 1

D-orbitals form cross shapes lobes that unify on the x, y, and z axis to produce a hypercubic model of the electron cloud

What is Ultraviolet Catastrophe? A harmonic solution to the Planck Constant.

When the classical interpretation of electromagnetism failed observational measurements of black body radiation, the Planck constant offer a solution to the Ultraviolet Catastrophe that suggested light was quantised into packets. However, an alternative solution can also be found in the nature of harmonic resonance.

Periodic Trianlge

Available now at the Da Vinci School